Denise Love, BACSA Projects Coordinator, reports on a new BACSA project at Dhaka, in Bangladesh:

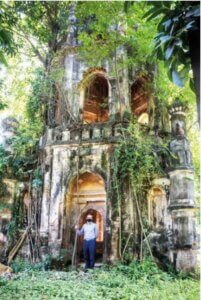

‘peeping through a canopy of

verdant foliage’ (Photo: City Syntax)

vegetation cut back and

details revealed

(Photo: Waqar Khan)

‘In the Wari Cemetery, sometimes called Narinda, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, there is splendid monument covering the graves of three people.

It is known as Colombo Sahib’s tomb, but nothing is known of such an individual. Even its date is not certain, but experts think it may be late 17th century.

The earliest image of it is a painting by Johann Zoffany in 1787. It is regarded by many as one of the finest funerary monuments in South Asia.

BACSA had for several years been trying to promote its preservation and conservation because it had been neglected and gradually taken over by trees – in a ‘vice-like grip‘, as can be seen in the photograph of Robert Chatterton Dixon, the then British High Commissioner to Bangladesh, who visited the monument in October 2020. Such a significant site could not be allowed to collapse and be lost.

Finally, at the beginning of this year our efforts began to bear fruit. In collaboration with the Christian Burials Board of Dhaka, BACSA’s area representative, Professor Ahmed of Asia-Pacific University, a noted conservation architect, produced a detailed specification for conserving the tomb.

(Photo: Waqar Khan)

(Photo: Waqar Khan)

BACSA has contributed £10,000, and the Commonwealth Heritage Forum has also made a substantial contribution.

The unrest in Dhaka this year and very heavy rains delayed the start of the work, but since the end of July it has progressed well under Professor Ahmed’s direction. Earlier this month Waqar Khan, Founder of Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies, and former area representative, wrote: ‘Just look at this! What is emerging looks simply spectacular! Eight years of relentless effort have finally paid off!’

The project is expected to be completed by March – April 2025.’

Denise Love

Editor’s Note:

Who was Colombo Sahib?

As Denise says, ‘the tomb is known as Colombo Sahib’s tomb, but nothing is known of such an individual’. In September 2016 Waqar Khan summarised current thinking in ‘The Enduring Enigma of Columbo Sahib’, an article published in the Daily Star. (As befits an enigma, the subject’s name is sometimes spelt ‘Colombo’, and sometimes ‘Columbo’).

An HEIC employee?

The name ‘Columbo Sahib’ first appeared in ‘Narrative of a journey through the Upper Provinces of India, from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824-5, with an account of a journey to Madras and the Southern Provinces‘ by Bishop Heber, the metropolitan Bishop of Calcutta, which was posthumously published by his wife Amelia, in 1828. After consecrating the Narinda cemetery at Dhaka during his 1824 Episcopal tour, Heber enquired about the imposing, but unidentified, monument. He zealously noted down the chowkidar’s Hindi reply ‘Yea Kalumbo Sahib ka maqbara, Kampany ka naukar’ (‘It’s the tomb of Columbo Sahib, a servant/employee of the East India Company’); but failed to identify this significant Christian personage.

From Ceylon?

Tim Steel, a British ‘amateur archaeologist, history buff and writer’ and former area representative, who once lived in Dhaka, strongly felt that Columbo Sahib was a prosperous merchant who had come to Dhaka from Colombo, and became known locally as Columbo Sahib.

Although speculative, Waqar considers this a plausible theory. He suggests that Columbo may have been a ‘Portuguese or Sri Lankan Sinhalese Christian who came to Dhaka from Colombo’, or perhaps a ‘local Luso-Portuguese gentleman from the Indian subcontinent’, and points out that the Portuguese connection is also supported by BACSA Committee member Charles Greig, who says: ‘I think it is also a very real possibility that Columbo was Portuguese – the translation of the name we know as Columbus is Columbo in Portuguese. At the time that the tomb was built (in my opinion) – c. 1670-80 – there was still a very strong presence of Portuguese traders in Dhaka. Moreover, the early Church at Narinda seems to have been Catholic.’

Or Holland?

However, another BACSA Committee member, Dr Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, has suggested that Columbo was probably sent by the Dutch East India Company from Colombo, Sri Lanka, to Dhaka to look after Dutch commercial interests.

Rosie points out that this tomb has a striking resemblance to the famous grandiose Mughal/Islamic style Dutch mausoleums in the old Dutch-Armenian-English cemeteries in Surat, India. In 2016 she wrote ‘my supposition that Colombo Sahib’s tomb may mark the resting place of a Dutch man is based on comparisons with the Dutch tombs in Surat, together with information that Dutchmen were sent to Bengal, from Sri Lanka (the capital Colombo in particular), to start textile trading from Dacca in the middle of the 17th century. We may never know, unless someone is prepared to go through the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) records at The Hague.’

In 2024 Rosie added: ‘I did investigate the possibility of this being the tomb of a Dutch person. There were Dutch governors in Bengal in the 17th century but a Dutch historian I contacted thought none of them were of sufficient importance to have commissioned a tomb like this. We don’t know the names of the Dutch Governors and unless someone is prepared to research the records of the Dutch East India Company in the Hague, we will probably never know. So my only reason for suggesting Dutch influence is the Dutch tombs at Surat’.

And the others?

Regarding the ‘other people’ buried under the monument, Charles Greig recently clarified: ‘The interior of the tomb has the headstones of numerous individuals – these are clearly rescued from other tombs long gone. But there are what appears to be three tombs on the floor of the tomb… (later covered with bits of old broken cut stone) as well as two of the broken minarets – we just do not know who these belong to as they are completely redone and no inscriptions remain’.

Conclusion

While conceding that ‘it is a fact that there is no other place in the entire subcontinent… except in Surat, where likeness to Columbo’s tomb can be observed’, Waqar considers it ‘most likely’ that Columbo Sahib was Portuguese, and may have come to Dhaka from Colombo, Sri Lanka or elsewhere. That he could have been Dutch ‘cannot be dismissed outright’; if his Dutch name was difficult to pronounce, and he came from Colombo, he may well have become known in Dhaka as Columbo Sahib.

Clearly, archival research in Calcutta, The British Library, the Hague and in Lisbon, is a pre-requisite for unravelling ‘the mystery of Columbo Sahib’. But even this may not provide an answer; as Waqar warns: ‘It is also quite possible that even after all the suggested research has been conducted, his identity may still elude us’. If that is the case ‘he will continue to be known just as before, simply as ‘Columbo Sahib’ of Dhaka, thereby remaining an enduring enigma well into posterity’.

1787

Rachel Magowan

(Suggestions for BACSA website news items are always welcome – please send them to ‘comms@bacsa.org.uk’)