And now, just as Hurricane Milton batters the coast of Florida, we have the following article on Cyclones at Coringa, Andhra Pradesh, by long-standing BACSA member Kevin Wells, from New Zealand. (An abbreviated version of this article appeared in the Autumn 2024 edition of Chowkidar).

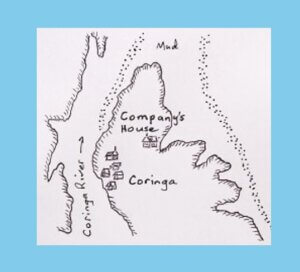

‘Historical maps are often a rich source of information and orientation for those with an interest in genealogical matters. Recently, I happened across an old sea captain’s chart which detailed the late 18th century maritime features of an area centred on Coringa, an Indian port facing the Bay of Bengal.

National Library of Australia

Entitled ‘An Eye Sketch of Coringa Bay on the Coast of Golconda’, the map, drawn up by Capt. Charles Lesley in 1774, and published in 1798, included an inset map of Coringa Bay, drafted by H.E.I.C. surveyor, Michael Topping, in 1789.

Trade in cotton textiles, timber, rice, spices and indigo once flourished along the eastern coast of India, and shipbuilding and ship-repair became major industries along the tidal banks of the Coringa River. For over 300 years, Dutch, French and English interests were often in conflict with each other over the control of this trade, and its associated ports and factories.

One particular feature on the map which caught my eye was the small drawing of a dwelling located above the mangrove-smothered banks of the Coringa River, adjacent to the main village of the same name. Described simply as ‘Company’s House’, it must surely be the enduring structure built by the East India Company for the accommodation of their resident Master Attendant in charge of this port.

(Joseph Conrad, 1902)

In his 1902 novella, ‘The End of the Tether’, the erstwhile seaman Joseph Conrad provides this job description: ‘A master-attendant is a superior sort of harbour master; a person, out in the East, of some consequence in his sphere – a government official, a magistrate for the waters of the port and possessed of vast but ill-defined disciplinary authority over seamen of all classes … miserably inadequate in that it did not include the power of life and death.’

A little harsh, perhaps, on someone whose job was to collect mooring fees, provide pilotage and row-boat hire, and to keep the local light-house well-stocked with oil, fresh water and food. A mounting increase in compulsory paper-work demanded by the Company irritated impatient, burly sea captains who frequently snarled at the ‘useless office’ of the master attendant.

But often such harbour-masters were indeed competent at their vocation: their actions prevented the destruction of vessels, and saved the lives of many caught on stricken ships. After 1850 medals were struck to honour such acts of bravery and decisive action by master attendants.

In April 1839, one of my ancestors, Charlotte Mary Innes, married James Flower Esq., (aged 26) in St Mary’s Church, Madras. James was one of seven children of Austin and Elizabeth Flower, whilst Charlotte was the youngest of General James Innes’ family of eight children.

At the time of his marriage James was a clerk of the peace (Madras Court). Following his appointment to the Master Attendant’s position at Coringa, he was granted a month’s leave to marry Charlotte, travel by sloop to Coringa, and settle into his new role.

1789: 1st Coringa Cyclone

I have described the ‘Company’s House’ at Coringa as an ‘enduring’ structure. I base this on the fact that fifty years earlier (1789) a terrifying cyclone smashed into this coast. Around 20,000 people were killed and damage was widespread. One report noted ‘the only trace of the ancient town (of Coringa) which now remains is the house of the master-attendant and the dockyards surrounding it.’

Coringa was never a salubrious place to live as the humid, low-lying coastal area was frequently inundated by storm surges and spring-tide flooding. Mangroves and mud-banks comprised a dreary landscape. In 1832 an easterly swell swamped the place ‘there being five feet of water in the master-attendant’s house and offices’. The port, and the house, must have been unpleasant places for Charlotte to live.

A lighthouse was built by the Company near Coringa in 1805 (remnants of which are still standing), but a second one was needed on the western shores of nearby Hope Island. This ‘island’ is a large, parrot-shaped sand-bar which still affords shelter for the Coringa Roadstead, where the semi-enclosed calm waters allow vessels to anchor safely when evading storms (or, in earlier times, having repairs carried out on the leaky hulls of wooden sailing ships).

By 1839 the Keeper of the 1816 Hope Island lighthouse was a young man named William Larkins Pascal. William and James Flower became good friends, and James is recorded as having rowed supplies out to William’s light-house several times a week.

1839: 2nd Coringa Cyclone

On 16th November 1839 an even more damaging cyclone, still regarded as one of the world’s greatest natural disasters, devastated Coringa. A 40-foot storm surge ‘ravaged far inland’, killing about 300,000 people, and wrecking around 20,000 vessels along the coast.

I regret not having any written word of this disaster from either James or Charlotte, but William Pascal made precise observations from the tower of his lighthouse during this tumultuous night. He recorded how a number of violent wind shifts were accompanied by a rise in sea level which inundated Hope Island. ‘At 10 pm, the wind hauled round to the SE and blew a dreadful hurricane during which the water rose to about 2 feet in the lighthouse, with a heavy confused sea beating against it, which burst open the door and swept away every article in it. At this time the top of the lantern wrenched and whirled itself aloft.’

William’s newly built house was completely washed away, along with every article it contained. He wrote that by midday on Sunday all was calm again, and ‘we found five corpses on the shore’.

Coringa was more or less abandoned after this event and new port facilities were developed further north at Cocanada, a harbour still within the protective wing of Hope Island. James continued his work as a master attendant (based at Cocanada after 1847), and the lighthouse on Hope Island was repaired, with William Pascal remaining in charge.

A personal tragedy befell James Flower not long after when Charlotte Mary died in June 1840, probably of cholera. The distraught husband was granted a month’s leave. It is believed that Charlotte is buried in a small cemetery at Coringa, where there are now only one or two headstones remaining.

Four years later, on 24th June 1844, a double wedding was celebrated at Coringa. The Rev. Lewis, chaplain from Masulipatam, officiated over the marriages of James Flower to Mary Rayneau, and William Pascal to Celestina Perry.

James Flower died at nearby Ingaram, near Yanam, in 1856, while William Pascal died at Vizagapatam in 1867’.

Kevin Wells

Ed. notes:

• Cyclones

The term ‘cyclone’ (Greek ‘κυκλων’, ‘coiling circulation of the winds’) first appeared in the 1848 book ‘The Horn-Book for the Law of Storms for the Indian and China Seas’, in which Henry Piddington, an East India Company official, and President of the Marine Courts of Inquiry, published the findings of his studies into several tropical cyclones, including both the Coringa cyclones of 1789 and 1839.

Piddington quotes from ‘a friend’, who visited Coringa about a month after the 1839 cyclone, and could relate facts which ‘would be thought travellers’ tales’, such as this one: ‘The number of vessels of from 100 to 200 tons that were high and dry miles inland, some bottom up, gave the country the appearance of having been visited by a party of gigantic demons, who had been throwing the huge hulls at one another’.

• A ‘dreary’ landscape? – Coringa today

Established in 1978, and described as ‘a paradise for nature and wildlife lovers’, the Coringa Wildlife Sanctuary on the Godavari estuary is the third largest stretch of mangrove forests in India, with over 24 species of mangrove trees, and 120 species of birds.

Rachel Magowan

(Suggestions for BACSA website news items are always welcome – please send them to ‘comms@bacsa.org.uk’)